Honorary Doctorate Awarded Resident of Remote Alaskan Village:

posted: May 10th, 2016 | by:Bert

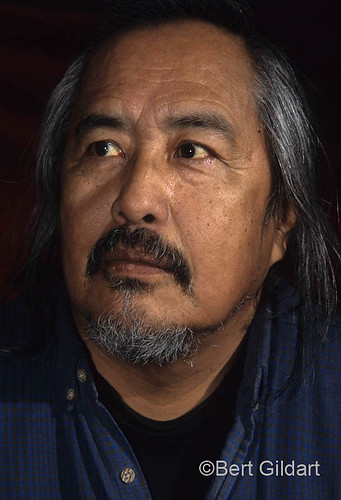

©Bert Gildart: This past Sunday (May 3, 2016), Trimble Gilbert of Arctic Village, Alaska, was presented an honorary Doctor Degree in Law for helping to advance the people of his village and for his efforts in helping to preserve the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

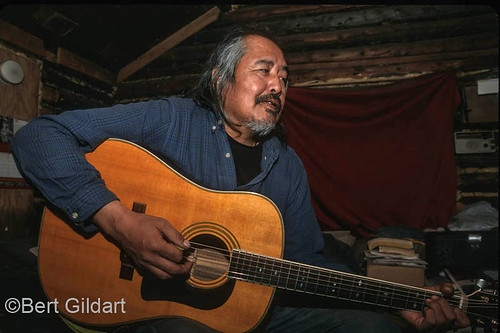

As well Trimble has served in his village as an Episcopal minister and a traditional chief. Not so incidentally he is one of the very best fiddle players in the entire Arctic region. Janie and I both feel privileged to know this man, and were once honored by Reverend Gilbert when he led his congregation in prayer intended to ensure our safe travels during a month-long hike through the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

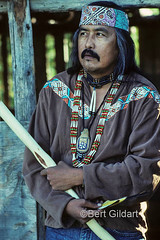

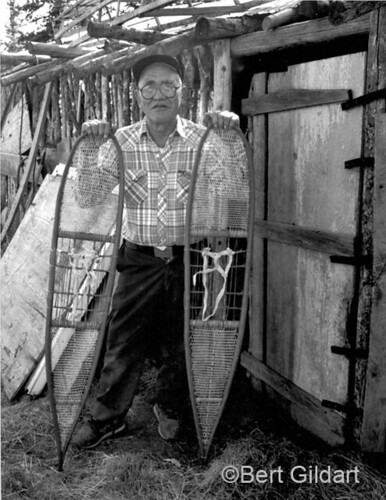

L to R: Trimble Gilbert has worn many hat during his life in Arctic Village, to include Episcopal minister and traditional chief; David Salmon presents

Trimble Gilbert with eagle feather and a Gwich’in Indian name to replace Anglo Saxon one; Trimble and Mary Gilbert in Arctic Village cabin.

Monday, April 9, the Fairbanks News Miner published an article which Gilbert had written, and I am excerpting portions of it here. Trimble is a most articulate man, and his views on education and on protecting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge are meaningful.

———–

WROTE DR. GILBERT IN the MAY 9 EDITION OF THE FAIRBANKS NEWSPAPER : As a boy growing up in Arctic Village, I learned by listening to my elders and taught myself to write by copying words from bags of sugar and flour. I never dreamed that one day I would receive an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from a university. But I never quit learning, and have spent my life encouraging young people to earn their degrees and make Alaska and the world a better place.

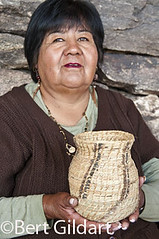

Education is the key to protecting Gwich’in culture, our way of life and the place where we live. For thousands of years, my people have called the Arctic home, subsisting on species such as fish from the Yukon River and caribou from what is now called the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Clean water and the wild landscape are essential to our survival.

For decades, I have fought to protect the Arctic refuge from oil and gas development because, to the Gwich’in Nation, wilderness is necessary for the survival of our people and our culture, and much of our food comes from the refuge. Preserving the refuge is a matter of human rights.

L to R: Tiny segment of Porcupine caribou herd stampede across Kongakut River;

the Arctic is not a BARREN wasteland as some politicians have proclaimed;

Johnathan Solomon, Trimble Gilbert share thoughts on refuge with Senator Max Baucus.

President Obama’s administration has recommended that Congress designate the coastal plain and other areas of the refuge as wilderness to ensure that the land will remain wild forever. We support this recommendation, because if drilling hurts the Porcupine caribou herd, the Gwich’in would likely disappear…

“Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit” is what we call the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge. This means “The sacred place where life begins.” The caribou come here every summer to birth their calves and nurse them until they are ready to migrate…

If drilling happened and affected the Porcupine herd — about 180,000 animals — its future would be threatened. And so would the Gwich’in people and our villages. If the caribou lose land, we will lose caribou. Without them, we cannot feed our families or teach our young people the traditional subsistence way of life. Our children will move to cities, and our community — and our culture — will cease to exist…

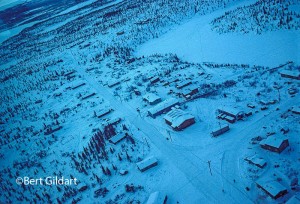

L to R: Hiking through Arctic National Wildlife Refuge with friend Burns Ellison; caribou

stand amidst field of Arctic Cotton; winter view from small plane of Arctic Village.

We are grateful to President Obama for recommending that 12.28 million acres of the Arctic refuge be declared wilderness and protected forever. This way we know all of the important land for the Porcupine caribou will be protected and the herd will not go the way of the great bison herds.

Trimble Gilbert with sons Gregory and Bobby, all excellent musicians.

The 19.5 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge are a treasure for all Americans…

—————

Janie and I have spent a number of years in the Arctic and believe that everything Trimble wrote in the paper is completely accurate. We’ll go one step further and say that the Arctic Refuge may well be the last self-regulating ecosystem in the world. The Gwich’in are the northern-most tribe of Indians in North America, living as they do at the base of the Arctic Refuge, located almost 200 miles north of Fairbanks.

————————–

HERE ARE A FEW OTHER POSTS ABOUT THE GWICH’IN INDIANS

4th ed. Autographed by the Authors

Hiking Shenandoah National Park

Hiking Shenandoah National Park is the 4th edition of a favorite guide book, created by Bert & Janie, a professional husband-wife journalism team. Lots of updates including more waterfall trails, updated descriptions of confusing trail junctions, and new color photographs. New text describes more of the park’s compelling natural history. Often the descriptions are personal as the Gildarts have hiked virtually every single park trail, sometimes repeatedly.

Hiking Shenandoah National Park is the 4th edition of a favorite guide book, created by Bert & Janie, a professional husband-wife journalism team. Lots of updates including more waterfall trails, updated descriptions of confusing trail junctions, and new color photographs. New text describes more of the park’s compelling natural history. Often the descriptions are personal as the Gildarts have hiked virtually every single park trail, sometimes repeatedly.

Big Sky Country is beautiful

Montana Icons: 50 Classic Symbols of the Treasure State

![]() Montana Icons is a book for lovers of the western vista. Features photographs of fifty famous landmarks from what many call the “Last Best Place.” The book will make you feel homesick for Montana even if you already live here. Bert Gildart’s varied careers in Montana (Bus driver on an Indian reservation, a teacher, backcountry ranger, as well as a newspaper reporter, and photographer) have given him a special view of Montana, which he shares in this book. Share the view; click here.

Montana Icons is a book for lovers of the western vista. Features photographs of fifty famous landmarks from what many call the “Last Best Place.” The book will make you feel homesick for Montana even if you already live here. Bert Gildart’s varied careers in Montana (Bus driver on an Indian reservation, a teacher, backcountry ranger, as well as a newspaper reporter, and photographer) have given him a special view of Montana, which he shares in this book. Share the view; click here.

$16.95 + Autographed Copy

What makes Glacier, Glacier?

Glacier Icons: 50 Classic Views of the Crown of the Continent

![]() Glacier Icons: What makes Glacier Park so special? In this book you can discover the story behind fifty of this park’s most amazing features. With this entertaining collection of photos, anecdotes and little known facts, Bert Gildart will be your backcountry guide. A former Glacier backcountry ranger turned writer/photographer, his hundreds of stories and images have appeared in literally dozens of periodicals including Time/Life, Smithsonian, and Field & Stream. Take a look at Glacier Icons

Glacier Icons: What makes Glacier Park so special? In this book you can discover the story behind fifty of this park’s most amazing features. With this entertaining collection of photos, anecdotes and little known facts, Bert Gildart will be your backcountry guide. A former Glacier backcountry ranger turned writer/photographer, his hundreds of stories and images have appeared in literally dozens of periodicals including Time/Life, Smithsonian, and Field & Stream. Take a look at Glacier Icons

$16.95 + Autographed Copy

Read Comments | Comments Off

Those of you who rely on the

Those of you who rely on the

Perhaps at this juncture, I should mention that you can catch many species of fish using very simple techniques, and pike are one of those species. Several years ago in Alaska, my wife and I spent the summer living out of a wall tent, traveling from hole to hole in our johnboat. In one case, we were cruising the waters for pike and had made a 70-mile trip from Circle down the Yukon to Fort Yukon where this sprawling river also accepts the Porcupine. Over the course of a week, we then proceeded 400 miles up the Porcupine River. It was hard, hard work, but you know the cliché; “Someone has to do it.”

Perhaps at this juncture, I should mention that you can catch many species of fish using very simple techniques, and pike are one of those species. Several years ago in Alaska, my wife and I spent the summer living out of a wall tent, traveling from hole to hole in our johnboat. In one case, we were cruising the waters for pike and had made a 70-mile trip from Circle down the Yukon to Fort Yukon where this sprawling river also accepts the Porcupine. Over the course of a week, we then proceeded 400 miles up the Porcupine River. It was hard, hard work, but you know the cliché; “Someone has to do it.” That’s a fly fishing technique, but you can also use a spinning rod and often do so more effectively than you can using a fly rod. But then, of course, you are no longer a purist. If that’s OK, and this time, you want to try for bass, begin by loading up your spinning rods with a rapallas or some crank bait, such as the Bomber 6A Red Crawfish or the Luhr Jensen Baby Hotlips (Don’t you just love these names!). You can also load them up with one of a thousand other lures, for the number of lures that have been created for bass fishermen is endless—and if the choices are overwhelming, you can easily simplify.

That’s a fly fishing technique, but you can also use a spinning rod and often do so more effectively than you can using a fly rod. But then, of course, you are no longer a purist. If that’s OK, and this time, you want to try for bass, begin by loading up your spinning rods with a rapallas or some crank bait, such as the Bomber 6A Red Crawfish or the Luhr Jensen Baby Hotlips (Don’t you just love these names!). You can also load them up with one of a thousand other lures, for the number of lures that have been created for bass fishermen is endless—and if the choices are overwhelming, you can easily simplify. Bert Gildart: This evening our cell phone broke the silence in our Airstream, and when we answered, we recognized the two Native American voices immediately, though we had not heard them now for months.

Bert Gildart: This evening our cell phone broke the silence in our Airstream, and when we answered, we recognized the two Native American voices immediately, though we had not heard them now for months. Though Kenneth and Caroline’s ancestors were all nomadic (Kenneth’s into the 1960s), amazingly, they have both advanced themselves in the “White-man way.” Still, they tend to prefer their own culture—and are sufficiently intelligent to walk whatever path they choose. Caroline, in fact, has earned a master’s degree and though the couple could have gone most anywhere in Alaska, they elected to return to Arctic Village, where she not only teaches, but serves as the village principal.

Though Kenneth and Caroline’s ancestors were all nomadic (Kenneth’s into the 1960s), amazingly, they have both advanced themselves in the “White-man way.” Still, they tend to prefer their own culture—and are sufficiently intelligent to walk whatever path they choose. Caroline, in fact, has earned a master’s degree and though the couple could have gone most anywhere in Alaska, they elected to return to Arctic Village, where she not only teaches, but serves as the village principal. Kenneth was referring to the time that he and I had driven two snowmobiles to Old John Lake on a day when temperatures hovered at about -30°F. (That’s a 70° temperature variation from where we are tonight in West Virginia). Length of day had diminished greatly and though we left at 9 a.m. darkness engulfed us for yet another hour. Nevertheless, we made the 20-mile trip in less than two hours. But that’s when the relatively easy work turned into some very, very hard work.

Kenneth was referring to the time that he and I had driven two snowmobiles to Old John Lake on a day when temperatures hovered at about -30°F. (That’s a 70° temperature variation from where we are tonight in West Virginia). Length of day had diminished greatly and though we left at 9 a.m. darkness engulfed us for yet another hour. Nevertheless, we made the 20-mile trip in less than two hours. But that’s when the relatively easy work turned into some very, very hard work. Such recollections are some of the memories we always enjoy sharing each time we visit, and that is generally quite often. As well we share memories from summer school teaching programs we both worked in and about a trip we made together down the Chandalar River, to the Yukon, and then 300 miles up the Porcupine River to Old Crow, Yukon Territories. What an adventure that was, stopping at various summer fish camps.

Such recollections are some of the memories we always enjoy sharing each time we visit, and that is generally quite often. As well we share memories from summer school teaching programs we both worked in and about a trip we made together down the Chandalar River, to the Yukon, and then 300 miles up the Porcupine River to Old Crow, Yukon Territories. What an adventure that was, stopping at various summer fish camps. Bert Gildart: We meet wonderful people along the road, all sorts of interesting people. But sometimes we meet people whose lives we admire and with whom we seem to share many similar experiences.

Bert Gildart: We meet wonderful people along the road, all sorts of interesting people. But sometimes we meet people whose lives we admire and with whom we seem to share many similar experiences. Just three years ago, Burns Ellison, a writer friend, and I had also taken this same boat and traveled from Fort McPherson just off the Dempster Highway but on the McKenzie River, to Aklavik, located not far from the Arctic Ocean. We reached this far-flung village by boating down the Peel Channel of the McKenzie River.

Just three years ago, Burns Ellison, a writer friend, and I had also taken this same boat and traveled from Fort McPherson just off the Dempster Highway but on the McKenzie River, to Aklavik, located not far from the Arctic Ocean. We reached this far-flung village by boating down the Peel Channel of the McKenzie River. But these were broad interests that we shared, and my familiarity, of course, was more through books, while Bob’s familiarity had been acquired through the history of the agency directly involved. As a member of the RCMP, he has certainly experienced hazards, and probably more than some of his contemporaries, as his specialty was drug control.

But these were broad interests that we shared, and my familiarity, of course, was more through books, while Bob’s familiarity had been acquired through the history of the agency directly involved. As a member of the RCMP, he has certainly experienced hazards, and probably more than some of his contemporaries, as his specialty was drug control.